Punctuated Geometric Monsters

Gould, Goldschmidt and Fisher walk into a bar. If you are not an evolutionary biologist, there is no way that any following punchline will be funny. The punchline, if there ever was one, would be more scientific than comical.

While there is no debate among scientists on if evolution has occurred, there is debate on how it does so. This point is sometimes misconstrued to portray evolution as just a theory that is not “proven.” But, overwhelming evidence from the fossil record to DNA molecules continues to show that the process of evolution has occurred, and continues to occur to generate the diversity of life on this planet.

In the popular discourse of evolution, there are several processes that often get mixed up. The specific process of evolution is not natural selection, and neither of them is speciation. Evolution, in its simplest form is change in a group of organisms over time (sometimes articulated as, descent with modification). You look different from your parents, you look more different from their parents, you look even more different from… and so on. Natural selection, on the other hand, is one possible mechanism for how the evolutionary changes occur. Imagine a single population of a pink flowered species of daisies. Over time flower color could change (evolve) from pink to yellow, but the population remains a single distinct species. This would be evolution (descent with modification) without speciation. The second question would be, what “drove” the evolution of flower color. This could either be natural selection or random processes (drift). For instance, if pollinators preferred yellow flowers and thus individuals with yellow flowers yield more offspring, yellow flowers could evolve through natural selection. However, we could also imagine a scenario where pink flowers change to yellow flowers from pure random chance. While it may be unlikely in this scenario I proposed, we could imagine that seedlings of yellow flowered plants just happened to survive more than pink flowered ones and then over time the pink flowered species would happen to evolve into a yellow flowered species. The engine of evolution in this second scenario would be drift, not natural selection. Speciation on the other hand is the process of one species splitting into two species. Evolution can occur without speciation ever taking place. Speciation always involves some evolutionary changes, even if those changes are not seen morphologically. While these processes are all intertwined, it is important to recognize their differences. These processes all hinge on a bit of luck, the size of the population, and the fitness benefits that each trait confers.

In August I wrote an essay on teratological events, or large mutations, that lead to major changes in the organism. Over the past few months, I have been reflecting on how major changes in evolution occur. In plants, we are very used to seeing mutations of large effect. For instance, most of our most prized flowers are what I call horticultural monstrosities, beautiful mutant flowers with many more petals than wild versions. Many garden plants have variegated leaves or weeping varieties. For anyone who cultivates plants knows, these mutants can occur rapidly in cultivation settings and we are primed to observe and select them. This essay focuses on two ways of thinking about major evolutionary changes and tries to link concepts from three prominent theories in evolutionary biology: Gould and Eldredge’s Punctuated Equilibrium, Fisher’s Geometric Model, and Goldschmidt’s Hopeful Monsters.

Double flower mutant of Westerland Rose (Rosa variety ‘korwest’). Usually roses have five petals, this plant was selected for developmental mutations that lead to multiple petals and a more beautiful display.

Double flower mutant of 'Blue Moon' Kentucky Wisteria (Wisteria frutescens variety 'Blue Moon'). Usually Wisteria have bilaterally symmetrical flowers with specific upper and lower petals. These mutants have abnormal flower development, making them beautiful and frilly.

A historically important question in evolutionary biology is whether evolutionary changes occur slowly and step-by-step (gradualism) or through large punctuated changes (sometimes referred to as saltationism). This is a problem that dates back to Darwin himself. He was a proponent of slow modifications through time, while his “bulldog” Thomas Henry Huxley cautioned against limiting consensus to one singular view and argued for a more pluralistic view of life. While this debate became largely one-sided (in support of gradualism) during the early 20th century, new molecular and mathematical data seem to be bringing renewed interest.

In 1859, the publication date of the Origin of Species, Darwin argued “Natura non facit saltum” nature does not make leaps. This phrase was one he often referenced—six times in the first edition of Origin. Darwin strongly opposed saltationism largely because in its nineteenth-century form, it implied sudden, discontinuous changes that bordered on divine intervention. Richard Dawkins emphasizes this in The Blind Watchmaker, using a ridiculous (but compelling) example of the instantaneous emergence of complex organs like an eye. Darwin viewed these saltationist explanations as antithetical to evolution by small, cumulative steps. In fact he argued that, “If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.” (Darwin, Origin of Species 1859 p. 189). This set the track for our modern view of evolution, the accumulation of small incremental changes generation by generation. No big leaps, no saltations.

This was solidified in what is now known as the “Modern Synthesis” during the first half of the 20th century, which was the merging of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection with a modern view of genetics and mathematics. Several concepts emerged from this synthesis. One powerful metaphor was the “adaptive landscape”, proposed by Sewall Wright. The adaptive landscape is a metaphorical topographic map, with peaks and valleys. Occupying a lower elevation on the landscape means an individual is less fit (reproduces less). Higher up means an individual is more fit, and when an individual is close to the highest local point, we can say they are at a fitness peak. Individuals can be placed on the metaphorical landscape based on their genetic makeup and relative fitness.

Another contributor of the Modern Synthesis, Ronald Fisher, was a mathematician—and a pretty damn good one at that! He essentially created modern statistics and population genetics. One of his many contributions was his “Geometric Model.” This model suggests that when a species is close to a fitness peak on Wright’s adaptive landscape, larger mutations are more likely to shift the lineage farther from the peak than closer to it. Rather, small mutations are mathematically more likely to move a lineage closer to the peak. Dawkins likens this to having a microscope that is nearly focused on the slide. Any large movement in the coarse focus of the microscope is more likely to get you out of focus (either higher or lower) than the fine focus would. Fisher’s Geometric Model reinforces, with the gold stamp of statistics, that gradual mutations of small effect size are more likely to lead to adaptation over time as opposed to large macromutations.

Enter Richard Goldschmidt, stage left. Goldschmidt was a geneticist and contemporary of Fisher and Wright in the early 20th century. He was made famous, perhaps infamous, for his idea of “Hopeful Monsters,” which was essentially a restructuring of saltationism. His work on mutant organisms led him to the hypothesis that the generation of new species (speciation) could occur through large macromutations affecting development, thus leading to abnormal teratological “monsters,” some of which are “hopeful” and selected for. His point was that manipulating genes affecting the developmental process itself could lead to large phenotypic effects. For instance, if you break a gene for flower color, you will have a rapid transition from pink to white flowers, and he argued this could lead to a new species. His work was vehemently bashed by organizers of the modern synthesis and Fisher’s math was used to support this bashing. They heralded the concept that small mutations lead to variation which spreads through populations over time—not macromutations abruptly leading to new species. This is true, and the math of Fisher's Geometric Model checks out. Given a consistent environment and stable population sizes, Goldschmidt's monsters were mathematically unlikely to result in a lineage that was more fit than its ancestor. Thus all, or most, macromutations will likely be deleterious (having negative implications for fitness).

However, work from developmental biologists is showing how single macromutations can lead to massive developmental shifts. For instance, in the iconic Stickleback fish (named for their spiny bodies) single mutations of large effect in regions of important developmental processes can lead to a complete loss of pelvic spines on these fish. Likewise, work on beach mice shows how a single mutation in a gene can lead to shifts in coloration patterns that are adaptive. While Fisher’s model suggests that large macromutations, even if they do lead to massive phenotypic effects, will not be selected for, we continue to see this in natural populations.

It is now time to introduce Stephen Jay Gould, an evolutionary biologist who, along with Niles Eldredge, coined the term Punctuated Equilibrium. This is a theory that has taken on many meanings and forms over time. In its most general sense, Punctuated Equilibrium suggests that lineages spend long periods of their history relatively unchanged (morphologically) and these long periods of stasis are punctuated by events of rapid evolutionary change. Rapid is the operative and dangerous word here. Some have taken rapid to mean within a generation and likened Gould and Eldredge’s hypothesis to a saltationist view, like Goldschmidt. However, rapid from an evolutionary perspective could still be hundreds to thousands of years—a time frame that is not measurable in evolutionary timescales, where we often deal with error bars in the millions. Indeed, Gould himself says, “the punctuations of punctuated equilibrium do not represent de Vriesian saltations, but rather denote the proper scaling of ordinary speciation into geological time.” (SJ Gould Punctuated Equilibrium p. 43). While Punctuated Equilibrium has sometimes been used to reject gradualism, it does not necessarily do so. Rather, the punctuated events of rapid change could be gradual, a phenomenon of long periods of stasis punctuated by more rapid events of normal gradual Darwinian evolution.

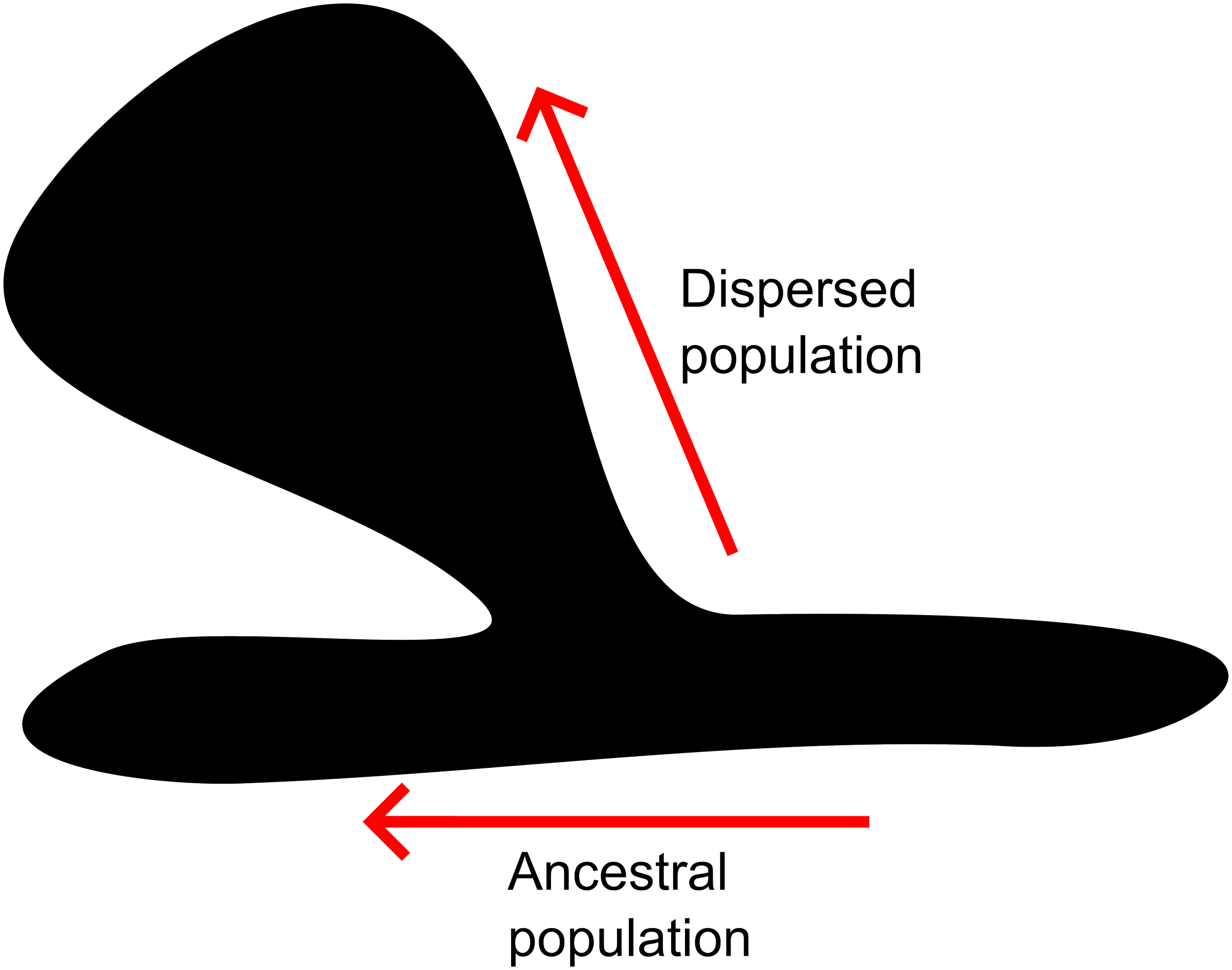

The important point of Gould and Eldredge’s Punctuated Equilibrium is that most evolutionary change occurs during punctuated periods of speciation, not along a single branch of a species. This is where it is important to return to the beginning of this essay and appreciate the differences between evolution and speciation. Gould and Eldredge argue that, while speciation is different from evolution, most evolutionary changes occur during speciation. They were not the first to prompt this idea, Ernst Mayr, another constructor of the Modern Synthesis, also suggested that most evolutionary change is likely to occur during periods of speciation. You could imagine that a subset of the ancestral population dispersed to a new environment. This new population then becomes genetically isolated from the ancestral one, so over time it diverges into a new reproductively isolated lineage (i.e., speciation). At the same time, because this new site is more likely to be different from the old one, the adaptive landscape shifts, and there are new selection pressures (maybe slightly different climate, new predators, or something of the sort). This would lead to the evolution of new traits in those new populations. This then recreates a new image of the speciation process, not of two equal branches, but if we weight the branch thicknesses by the amount of change from the past, it would yield a skinny ancestral branch and a thick lateral branch. The lineage that dispersed to a new environment would be much more likely to change than the ancestral population.

Diagram showing how the dispersed population can change more than the ancestral population. Each branch on the “blebogram” represents a population. The width of the branch relates to the amount of change relative to the ancestral population. The main branch (lower branch) represents the relatively unchanged ancestral population. The wider upper branch represents the dispersed population.

So, how do we merge Punctuated Equilibrium, Hopeful Monsters, and Fisher’s Geometric Model? Recent mathematical models suggest something quite interesting. Work by McDonough and Connallon in 2023 (and Orr in the 1990s) suggests that when the adaptive landscape remains constant (e.g., the environment does not change) and population sizes do not change, Fisher’s math is solid, small changes are more likely to fine-tune traits, get a lineage closer to adaptive peaks, and spread through a population. However, McDonough and Connallon mathematically demonstrated that when population sizes decrease and when the adaptive landscape changes, larger macromutations may be favored. These decreases in population size and shifts in the adaptive landscape can occur through large climatic events like a volcanic eruption or asteroid impact, but also from dispersal events to new environments. In both cases, the population size is dramatically reduced and the landscape altered. Mathematically, then, macromutations (in a truly rapid manner) may potentially be favored under these periods of dispersal (and speciation events) or rapid ecological change when the environment has shifted and population sizes are generally lower.

It is possible, now, to imagine a scenario where a population disperses to a new environment, the landscape shifts and the population size decreases. Then, it is more likely that a new mutation modifying a developmental program, can lead to a massive shift in phenotype (a monster). If, perhaps, that phenotype happened to be adaptive that new mutation could spread in the population. This could happen in a relatively small number of generations if the population is small enough and the new fitness landscape different enough. This was recently empirically demonstrated by Battlay and colleagues in annual ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), the plant that causes hay fever. The species is a weed with many individual introductions to new environments. By sequencing the genomes of individuals of newly formed populations they found that during times of dispersal where population sizes decrease and the environment shifts, new populations have “large-effect structural variants” or massive mutations, particularly huge rearrangements of their chromosomes. These large variants meant the invaders were more fit in their new environment. One interpretation of these populations is, indeed, Goldschmidt’s Hopeful Monsters.

Thus major leaps in evolution could occur truly rapidly (within a few generations) during periods of dispersal and thus periods of incipient speciation. If these changes occur through large macromutations that affect developmental processes, we could describe these new lineages as “monsters” relative to their ancestral form. Thus, it is possible to reconcile an evolutionary scenario where Punctuated Geometric Monsters exist.

During normal periods of time, these macromutations are not likely to be selected for based on Fisher’s Geometric Model, but based on new mathematical models it is possible for large macromutations to spread. These macromutations could lead to limited morphological changes but massive physiological ones, or they could be shifts in the developmental processes leading to major morphological changes that, in the fossil record, would look like punctuated shifts (e.g., the original interpretation of Punctuated Equilibrium).

I am not arguing that evolution occurs exclusively through these means, but it is an additional process that mounting evidence suggests can, and has, occurred. Like Huxley, why can’t we have a more pluralistic view of life? Mutations of small effect are the bread and butter of evolution by natural selection. The Fisherian model has not failed us. However, more data are showing us that there may be a plurality of ways lineages evolve. Maybe most often it is in small bursts, but every once in a while it can be large, if the population size decreases and the landscape shifts. Long live Punctuated Geometric Monsters.

References and further reading

Battlay, Paul, et al. "Rapid parallel adaptation in distinct invasions of Ambrosia artemisiifolia is driven by large-effect structural variants." Molecular Biology and Evolution 42.1 (2025): msae270.

Chouard, T. Evolution: Revenge of the hopeful monster. Nature 463, 864–867 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/463864a

Eldredge, Niles, and Stephen Jay Gould. "Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism." Models in paleobiology 82 (1972): 115.

Fisher, R. A. (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Hoekstra, Hopi E., et al. "A single amino acid mutation contributes to adaptive beach mouse color pattern." Science 313.5783 (2006): 101-104.

McDonough, Yasmine, and Tim Connallon. "Effects of population size change on the genetics of adaptation following an abrupt change in environment." Evolution 77.8 (2023): 1852-1863.

Orr, H. Allen. "The population genetics of adaptation: the distribution of factors fixed during adaptive evolution." Evolution 52.4 (1998): 935-949.

Wucherpfennig, Julia I., et al. "Evolution of stickleback spines through independent cis-regulatory changes at HOXDB." Nature Ecology & Evolution 6.10 (2022): 1537-1552.